What Exactly is a Misinformation Researcher?

Misinformation is a broad term and often misunderstood, so I wanted to describe what kind of work I do.

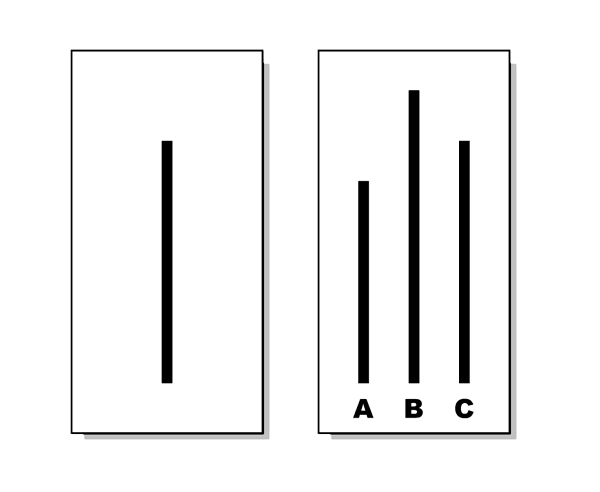

The Solomon Asch conformity studies were experiments done in the 1950s that showed how people are influenced by the opinions of a group, even when those opinions are clearly wrong. One of his classic studies involved a group of people seeing a line and then they were asked to match its length to one of three other lines. The answer was obvious, but in the group, only one person was a real participant. The others were actors who were told to give the wrong answer on purpose. When the actors all gave the wrong answer, the real participant often went along with the group, even though they knew the answer was wrong.

As an undergrad, I studied psychology, and I was fascinated by the Asch conformity studies when I learned about them. I also became very curious about how psychological bias influenced both myself and those around me. This curiosity ultimately led me to graduate school, where I focused on studying how social and psychological processes shape our beliefs and behavior. As a graduate student, I published a paper exploring the relationship between our social networks and the strength of our beliefs. I discovered that having just one person in our network with different political or religious views significantly weakened the strength of certain beliefs, particularly those related to American politics and Christianity.

Over the last few years, I’ve been studying how various social and psychological factors influence susceptibility to misinformation. Misinformation is a broad umbrella term that refers to false or misleading information, regardless of intention. Hoaxes, scams, deepfakes, propaganda, and fake news are all types of misinformation. Misinformation has been an academic term that has been studied in social science for decades. For example, the “misinformation effect” gained a lot of popularity in psychology in the 1980s, and it deals with how exposure to false or misleading information can bias what we remember from certain events. This phenomenon connects to a broader literature on psychological bias and information processing.

In a 2024 article, I studied how personal networks predicted belief in “misinformation.” My study had both Democrats and Republicans read short political rumors that made their own political group look good or bad (e.g. a Democrat/Republican bullied or helped someone). I also had them read completely fabricated news headlines that denigrated their opposing political group. For example, the headline “Donald Trump Jr. Sets The Record For Most Tinder Left-Swipes in One Day” was being shared on social media and attacked a prominent Republican, but it was completely made up. I found that both Democrats and Republicans were more likely to believe and share these made-up rumors and false news stories when they supported their own political group or attacked the opposing group. I also found that just having a single person in your personal network who had different politics than you significantly decreased the likelihood of believing and sharing these types of misinformation. Finally, this study found that when people's social networks are more uniform, they tend to feel a stronger connection to their political identity, and this can reinforce biased beliefs about their own political group and those they see as opposing it.

So, while I study “misinformation” at a broad level, the more specific way to describe my research is that I study how social identities and personal networks influence information processing and decision-making. Since we are social creatures, we have a motivation to protect our social identities, and this can bias us to interpret information in a way that supports them even if it’s not entirely accurate. This is true for any social identity and sports fandom is a good example. We can think about how we are more likely to believe a referee made a bad call against our favorite team. Political identities can affect many types of information, and they have a clear ingroup and outgroup in the United States, which makes them pretty straightforward to study in social science!

My research is not about censoring people or dictating what they should believe. I don’t work with social media companies to attempt to regulate content. Instead, my work focuses on understanding how our social connections and identities shape how we process information. Understanding these processes helps us make better decisions in an increasingly complex information landscape. My most recent work has focused on teaching these skills directly through media and digital literacy.

My colleagues and I created a WhatsApp-inspired game where you learn how to identify hoaxes and scams you might see online (such as a financial scam or a rumor about a wild animal in the city). We found that people who played our game were better at discerning fabricated headlines and more cautious about their online sharing behavior. In another recent study, we helped people better identify fake images after they read short strategies on how to spot image manipulation techniques. This work broadly falls under the umbrella of “misinformation research,” with the ultimate goal of empowering individuals to critically evaluate the information they encounter online. By understanding these underlying forces, we can become more informed, discerning, and thoughtful in how we consume and share content.

Hi Matthew,

Good article, and the game looks like a very useful tool to jumpstart more critical ibformation consumption. Just a heads up, though. When I click the link to head over to the game I get an "unsafe site" warning. It seems your site certificate expired 4 says ago. They can be a minor pain in the butt to maintain, but might be worth just dealing with it.